News

Opinion: Statues are Good to Think With

October 2018

By John Lutz

Statue of Sir John A. Macdonald at Victoria City Hall.

Recently there has been a movement to take some of the heroes of Canadian history off their pedestals and remove their names from buildings, schools and streets. John A. Macdonald’s statue has been removed from the city hall of Victoria BC, an area he represented as the Member of Parliament; Ontario teachers have called for the renaming of schools named for our first Prime Minister; Edward Cornwallis has been toppled from his pediment in Halifax. From coast to coast, there clearly has been a sea-change in how we see historical figures. Should we be re-naming and destatuing as steps towards reconciliation and if so, how far should we go?

These questions have spurred the History Department at the University of Victoria to organize a series of public forums, one on the politics of renaming and destatuing and a series of others examining the legacy of Macdonald and other historical figures who are now controversial, to put their lives in the context of their times.

While the recent flurry of interest was spurred by American controversies over statues of Confederate heroes, these forums reminded us that the practice of renaming and destatuing is not new. Many historical ruptures such as the defeat of Hitler, the end of the Soviet Union, the overthrow of Saddam Hussein in Iraq, end of Apartheid in South Africa, not to mention more ancient examples, have prompted wholesale reshaping the landscapes of iconography and nomenclature.

Dr. John Lutz, professor and chair of the History Department at the University of Victoria has spoken at a number of these forums. He agrees that there are situations when a consensus is achieved that social values have changed, and it is appropriate to rename or depose statues. However, he argues that, in most cases, it is better to leave these reminders of the past - and use them to “think with” about our past. He argues that a statue or a name, while they may have been placed to honour, are not inherently honorific. A statue and a place name, he says, are merely reminders and invitations to recall a historical figure or event and tell a story about them. Once a statue or a name is in place, its meaning has escaped the intent of the erectors or namers and passes into the hands of passers-by, visitors and occupants. The stories the statues point to, can change over time even if the statue remains the same and the same statue might invoke different stories for different folks.

According to Lutz, the statue of John A. Macdonald reminds us to tell stories about the man who played a key role in the founding of Canada, but we get to choose which stories. Even the academic histories change, so that the stories that historians tell are different now than forty years ago when the Victoria statue was erected. Today historians see Macdonald as an important but flawed character who, in the process of creating a new country was instrumental in displacing the Indigenous people who owned the land Canada is built on. To Canadians he is a symbol of nation and national pride. At the same time, Macdonald is a symbol of embarrassment and shame for his attitudes and the legislation he promoted which denigrated and harmed First Nations and immigrants from Asia. A statue of Macdonald is a reminder to tell all or any of these stories. Rather than displacing these bronze and granite reminders to tell stories about our past, Lutz suggests that we can add commentary to them and, better still, add new monuments that prompt us to tell new stories.

“Statues are mute.” Professor Lutz says, “They are reminders to think critically about our past but it is us, today, who get to tell their stories.”

New Teaching Guide – Umiaqtalik: Inuit Knowledge and the Franklin Expedition

June 2017

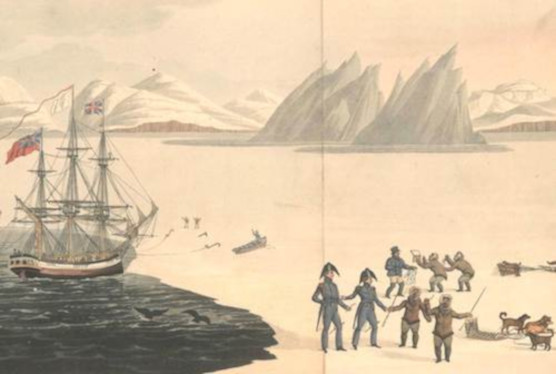

"First Communication with the Natives of Prince Regents Bay" as Drawn by John Sackheouse and Presented to Captain Ross.

We are pleased to announce that educators can now download a new teaching guide from our website. Just sign up here if you have not already registered to get free access to our teaching materials.

Umiaqtalik: Inuit Knowledge and the Franklin Expedition is a new teaching guide developed by the Dept. of Education, Government of Nunavut, in collaboration with the Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History Project. The Government of Nunavut was one of the partners in the development of the website The Franklin Mystery: Life and Death in the Arctic.

Paul Quasar, formerly Minister of Education for Nunavut and later premier, speaking at the launch of The Franklin Mystery website in June 2015. (Jake Wright)

The guide, available in Inuktitut and English, was designed for grade 8 students in Nunavut. There are notes throughout the document about how to adapt the unit for use in other contexts.